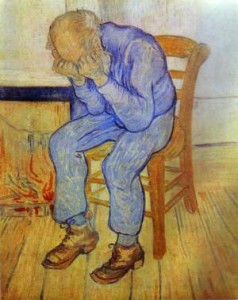

Grieving is a highly underestimated core capacity of becoming human. Ungrieved heartbreak accounts for much in our life that never seems to change despite our best efforts. Until the heart releases the trauma that caused the heart to break in the first place, whenever we are faced with a situation in life that remotely resembles the trauma we won’t be able to respond in freedom. We will respond in concert with the compensation strategies we developed so that we won’t be hurt again.

Grieving is a highly underestimated core capacity of becoming human. Ungrieved heartbreak accounts for much in our life that never seems to change despite our best efforts. Until the heart releases the trauma that caused the heart to break in the first place, whenever we are faced with a situation in life that remotely resembles the trauma we won’t be able to respond in freedom. We will respond in concert with the compensation strategies we developed so that we won’t be hurt again.

Fear of grief freezes the evolutionary process. It is a competency that is particularly challenging for men, because it requires that we make friends with vulnerability. We have been socialized away from vulnerability because of gender constructs that have little to do with being human.

There is much to grieve. We live in a time when our species feels fundamentally separate from Earth and the universe itself. Modernist consciousness cultivates the illusion of separation. To a degree that we are mostly unconscious, because it is simply the water we swim in, we assume that we are alone and isolated in an uncaring universe. We live in a sea of hyper-individualism in the Western World, which has eventuated in a neo-liberal, hyper capitalist economic system that is devastating our planet. As ecologist, Joanna Macey, has been pointing out for decades the first step in our recovery as human beings is grief for our home, our beloved planet Earth. Beneath our grief, waiting to be felt and enacted, is an overwhelming love and gratitude and devotion to our beloved home planet.

The same is true in our personal lives. We arrived on this planet with a promise we were hoping to collect on. That is the promise of unconditional love. This is what we were expecting to give and receive—that deep sense of being in loving relationship with All That Is. Every failure of love, for this reason, is shocking. These failures can be subtle, such as the realization that the Other is not attuned to our feelings, to gross, such as physical and emotional abuse.

We often assume that if the failure of love was not gross and unconscionable that we have nothing to complain about. But our hearts are very sensitive instruments of the soul. We should be careful about judging too quickly whether the insult to our dignity was severe enough to have impacted us so deeply. Perhaps we heard our parents say to us, when we were crying, “Straighten up, or I’ll give you something to complain about!” We learn to simply endure our suffering, when the human thing to do is to grieve.

When we consider the human imperative and opportunity to love one another we wonder why it is so difficult. It’s what we all want, more than anything. We’re hardwired for it, and yet we’re all suffering from failures of love. The truth is that the roots of this failure reach back thousands of years. Each of us who are born into the 20th and 21st century inherit the evolutionary history of an entire universe, both good and bad. This includes the human history of violence. It is not a pleasant history, and there are many theories, beyond the scope of this post, about its origin (from the advent of agriculture, the rise of patriarchy, and the denigration of the feminine—all related in my opinion). There is a social history of war, pillage and rape, sexual abuse, and physical violence in society at large—that is reflected in families—that is part of that evolutionary inheritance. While the doctrine of the fall, in the Christian lineage, is usually distorted, it does accurately reflect (not that something is inherently wrong with us) but that we are born into, and therefore affected by, this history of violence.

It is not an exaggeration to say that when we begin to open to our own grief, we are also opening our hearts to this cultural history. When we open to our own grief we begin to open our eyes to the impact of this history all around us—in our families, in the guy sipping coffee next to us at the cafe, in the woman who is treating her dog so miserably, in video clips of the refugee crisis in Syria. The impact is all around us, in the way we tacitly assume and capitulate to the way things are structured in our social, political, economic, food, and security systems. We awaken to the truth that we truly do live in the Matrix, that we are following a program not of our making. We begin to believe that the goal of life is simply to achieve sufficient financial security to buffer us against the harsh reality others are facing.

It is not uncommon for those who have used psychedelics, particularly LSD, to tap into grief over the collective violence over millennia. Christopher Bache, an intrepid psychonaut, who employed LSD over 20 years, in a very intentional way (Diamonds from Heaven), was taken into this space of collective grief. His willingness to face into this dark reality is similar to the Buddhist practice of compassion. Here, the meditator opens in compassion (which is to grieve) for the history of violence, and contains it all. In this way, I believe, the practitioner participates in a redemptive project.

I have worked with many clients, who in the process of therapy, realize that they were unconsciously using their spouse/partner to fill in the residual emotional deficits from childhood. The spouse feels intuitively that something is not right. It’s as though too much is being asked, and that is true. When this is spotted, I will intervene and lovingly let the person know that they can never make up for what they didn’t receive as a little one. Thus ensues grief. The person is then able to take responsibility for the deficient and even learn to self-parent. But even this self-parenting, (loving of self), does not relieve the original grief. Rather, it integrates it, and we become friends with sorrow. The spouse will feel relieved that s/he is not being expected to make up for failures of love that s/he had nothing to do with.

Grief, personal and collective, opens our eyes just as it opens our hearts. As our hearts open, we begin to fall in love again with life. As our eyes open, we increasingly become outliers, starting to question reality as it is constructed. If the goal of a psychotherapeutic process is limited to personal healing, it is little more than an opiate that keeps us functioning in the Matrix. Awakening, effected through the courage to grieve, is about touching into the longing for “the better world that our hearts know is possible” (Charles Eisenstein).

Grief is a way to reset our default system to remaining human in a world that is rapidly forgetting what that means. It gives us the capacity to shudder at evil, when we are in danger of becoming inured to its presence, to love our intimates more deeply, when we had almost given up on it, to celebrate more deeply, to feel more tenderly, and to connect more deeply to the world around us. Our compassion is reawakened because when we lose our fear of grief and allow it to have its way with us.